We use AI every day, but do we really know how it works under the hood? Most of us probably don't. So in this post, I'm going to try to break it down as simply as possible.

A bit of context before we start: I'm just like most of you reading this — not an AI expert, just someone who uses these tools constantly in my day-to-day work. I rely on them a lot to be honest. And more than once I've thrown a prompt into ChatGPT, gotten something completely off from what I expected, and sat there wondering, "How do you misunderstand this and still call yourself 'intelligent'?"

That frustration pushed me to dig deeper. Eventually, I stumbled onto a 3.5-hour lecture from Andrej Karpathy. Andrej is one of the clearest teachers in the AI world, and this video is basically a must-watch for anyone who wants to actually understand how large language models (LLMs) work. It's a mandatory first lecture — the same way that, if you study economics, the very first thing you get introduced to is supply and demand. You can't skip it. Everything else makes more sense afterwards.

So in the sections below, I'll break his talk into bite-sized pieces and explain the core ideas in normal, approachable language.

How Models Learn From the Internet?

Before a model can answer our questions, it first goes through something called pretraining — basically, it reads a massive amount of text from the internet.

The big players — OpenAI, Anthropic, Google, Meta, and others — all start in a similar way: they collect massive piles of publicly available text.

A good example of how this actually works is a dataset called FineWeb, built by Hugging Face. It's one of the most transparent, publicly documented examples of how these internet-scale datasets get made. If you're curious about the nitty-gritty, it's worth a look.

Where the data comes from?

Most teams start with something like Common Crawl — an organization that's been scanning the web for years and collecting billions of pages. This raw data includes everything: articles, blogs, forums, and a lot of stuff you definitely don't want in a training set.

To turn that mess into something usable, companies run a bunch of filtering steps:

- Remove unwanted sites

Things like spam, malware, obvious SEO junk, shady content, or sites with sensitive material get dropped. - Keep only the readable text

Webpages are full of HTML, menus, ads, sidebars, and scripts. All of that goes away. What remains is the main text a person would actually read. - Filter by language

Datasets like FineWeb mostly keep English pages. That choice matters: if a language is mostly filtered out here, the model later won’t be very good at it. - Drop duplicates and personal data

Repeated pages and anything that looks like personal information (addresses, phone numbers, IDs, etc.) are removed.

After all this, they end up with a large, cleaned-up text dataset. FineWeb, for example, is around 44 terabytes of text. It sounds huge, but that can fit on a single modern hard drive. Once you strip out images, video, styling, and junk, the remaining text from the internet is big, but not infinite.

What does the final text actually look like?

In the end, it’s just text. A mix of:

- news articles

- how-to guides

- explanations and FAQs

- scientific notes

- random blog posts and forum threads

All of that becomes the starting point for training the model.

If you took just the first 200 cleaned web pages, you’d already get a massive wall of text. Now multiply that by millions. That’s the kind of material a model has read before it ever talks to you.

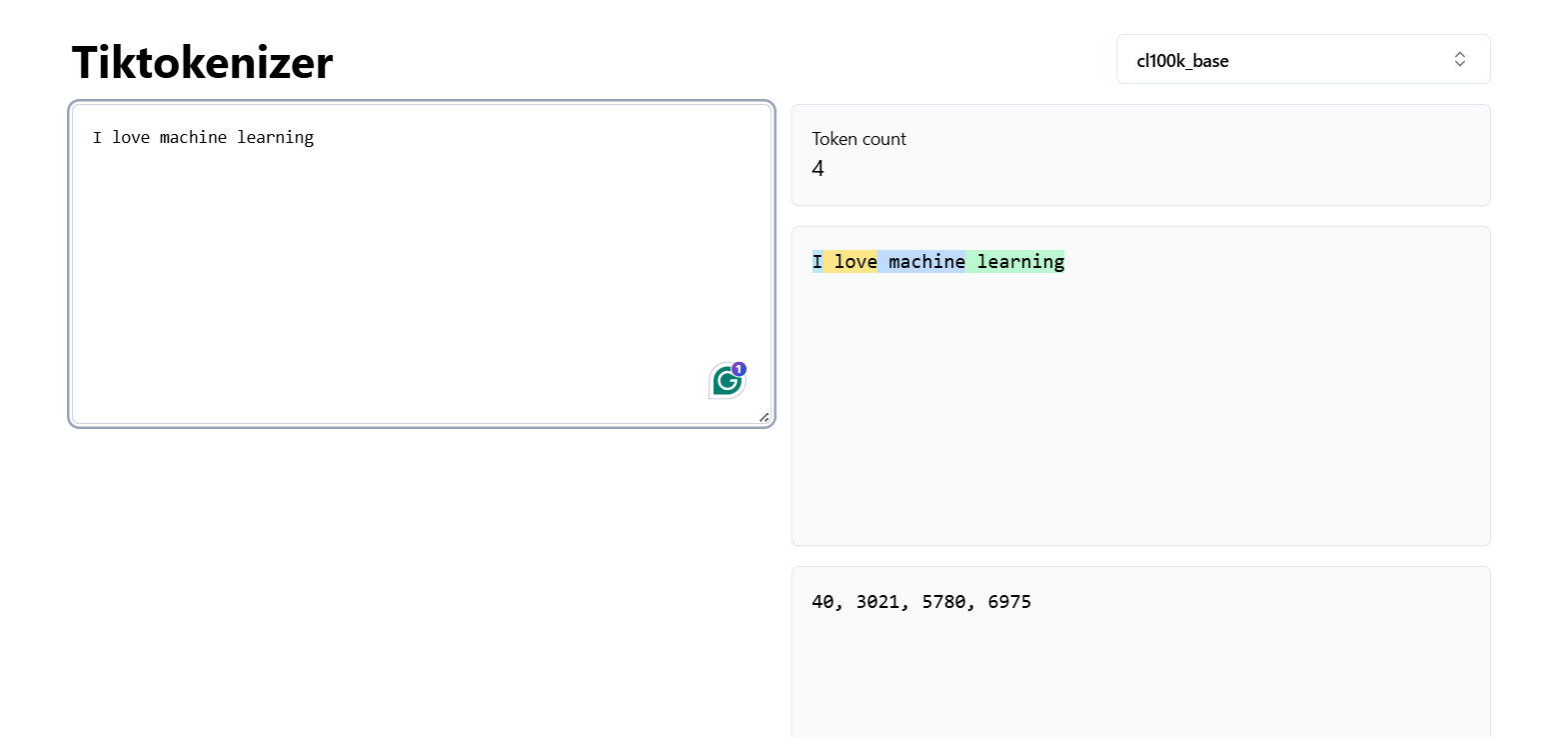

Tokenization: Turning Text Into Something a Model Can Actually Understand

Before a model can learn anything from text, it has to break that text into small pieces called tokens. It’s not reading words the way we do. It’s working with a long string of tiny chunks — sometimes whole words, sometimes parts of words.

For example, the sentence:

"I love machine learning."

might turn into something like:

["I", " love", " machine", " learn", "ing", "."]

Or in numbers: 40, 3021, 5780, 6975

It looks odd, but this is the format models understand. Every token is mapped to a number, and those numbers are what flow through the network during training.

This matters because:

- Models don’t “see” text — they only see tokens.

- Long words, rare names, or emojis may break into many tokens.

- The cost of running a model and the limits of a model’s memory (its context window) all depend on how many tokens you give it.

One thing that’s useful to know while we’re talking about tokens:

LLMs don’t plan their whole answer in advance — they generate it token by token.

Every new token is another tiny “step of thought.”

So if an answer is long or complicated, the model is literally working through it piece by piece as it writes.

That’s why:

- longer replies feel slower

- hard questions need more reasoning steps

- some models perform better when you let them “think out loud”

You can imagine it like watching someone solve a problem while speaking — the thinking and the talking happen at the same time.

Once all that text from the internet is chopped into tokens, the model finally gets to learn something from it. This stage is called pre-training, and it’s basically the model’s long, painful study session.

Here’s the simple version:

During pre-training, the model reads billions of tokens and keeps playing the same game over and over:

“Given the tokens so far, what’s the most likely next token?”

That’s it.

That’s the whole job.

It doesn’t learn rules.

It doesn’t learn grammar charts.

It doesn’t store facts in neat folders.

It just gets incredibly good at predicting the next token based on patterns it has seen before.

Think of pre-training like this:

- If it reads a lot of news articles, it gets good at news-style writing.

- If it reads tons of Python code, it gets better at finishing code.

- If it reads enough conversations, it picks up the rhythm of dialogue.

At this point, the model isn’t “smart.” It’s not helpful, polite, structured, or even safe.

It’s just a giant pattern-predictor that learned from a messy mix of internet text.

The key idea:

Pre-training gives the model knowledge, but not behavior.

It knows things in a fuzzy way — but it doesn’t yet know how to talk to humans.

That part comes next, during inference and post-training.

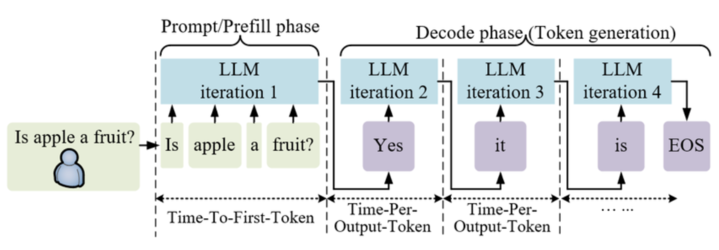

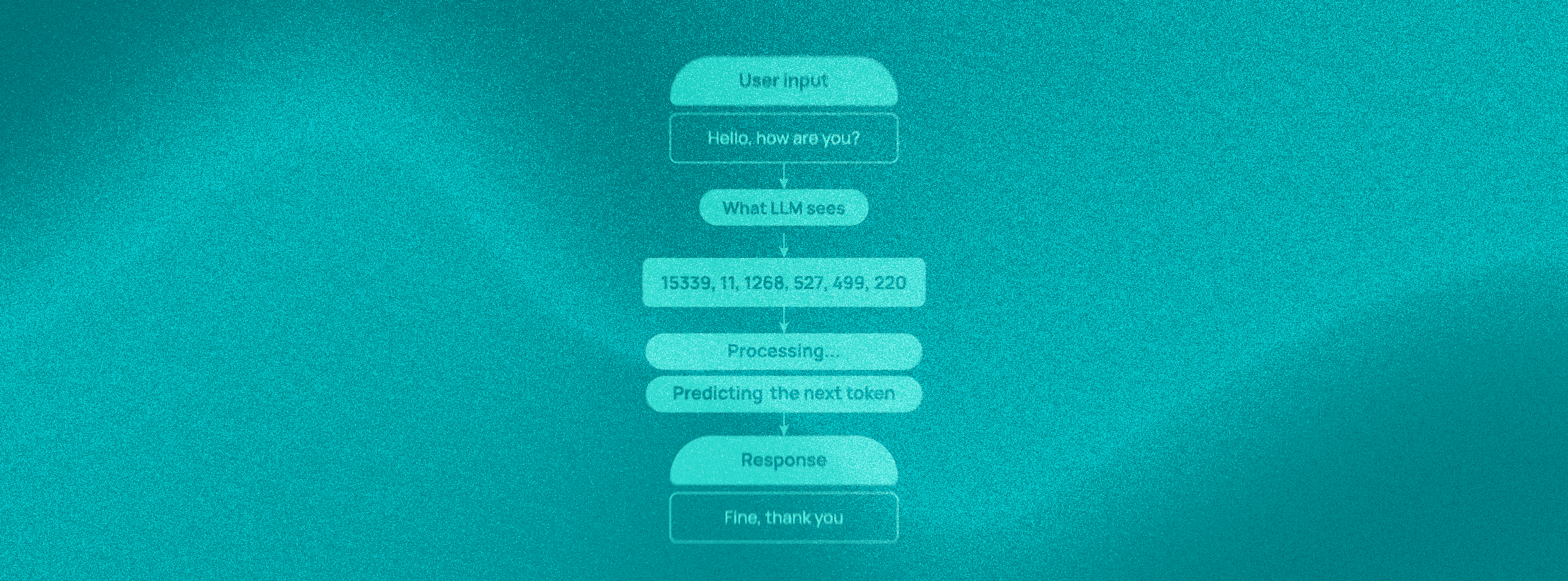

Inference: How a Model Generates the Next Word?

Now that the model has already done all its studying during pre-training, the next stage is what you experience every day when you type into ChatGPT: inference.

Inference is just the model running — taking what you wrote, predicting the next token, then the next one, then the next one… until it forms a full answer.

Here’s the simplest way to think about it:

- You give the model some text — a question, a paragraph, a half-written sentence.

- The model turns that text into tokens.

- It predicts the most likely next token, based on everything it learned during pre-training.

- That new token gets added to the input.

- It predicts the next one.

- And the next one.

- Repeat until it looks like a complete answer.

It’s basically autocomplete on steroids.

A key point:

Inference is not learning.

The model isn’t improving, changing its knowledge, or updating its memory.

It’s just using the fixed patterns it learned long ago to guess what comes next.

And because it’s sampling from probabilities — not following strict rules — two runs of the same prompt can give slightly different outputs. Sometimes it sticks close to what it has seen before. Other times, the “coin flip” at each token leads to a different path.

This is also why models can suddenly jump into unexpected ideas or phrasing. One small token sampled differently early on can push the entire answer into a new direction.

To summarize the whole idea:

Pre-training teaches the model.

Inference is the model performing.

Everything you see on ChatGPT — every answer, rewrite, idea, poem, email, or explanation — is the model predicting tokens one by one, extremely fast.

Post-Training: Teaching the Model to Act Like a Helpful Assistant

By the time a model finishes pre-training, it knows a ridiculous amount of stuff — but it doesn’t behave.

It’s basically a teenager who has read the whole internet but never learned how to talk to people.

That’s where post-training kicks in.

And this stage is where companies like OpenAI, Anthropic, and Google put in the real polish.

It’s the reason ChatGPT feels nothing like a raw model dumped straight from the internet.

Post-training has three main parts.

A. Supervised Fine-Tuning (SFT): When Humans Show the Model “How It Should Act”

Big labs literally hire teams of people to write example conversations that demonstrate what a great answer looks like.

Things like:

- clear explanations

- polite clarifications

- refusing unsafe requests

- helping without rambling

- following instructions step-by-step

In other words:

“Here’s how a helpful assistant responds.”

The model goes through millions of these examples and starts picking up:

- tone

- structure

- pacing

- how to be helpful instead of chaotic

This is the “manners” phase.

Raw models don’t talk like ChatGPT.

ChatGPT talks like ChatGPT because humans trained it to talk that way.

B. RLHF: When Humans Teach the Model What Feels Better

RLHF (Reinforcement Learning from Human Feedback) is the magic trick behind why modern models:

- stay calm

- stay polite

- avoid giving harmful answers

- ask clarifying questions

- don’t argue or snap back

- try to be genuinely helpful

The process is basically this:

- The model generates two possible answers to the same question.

- Human reviewers choose which one they prefer.

- The model gets “rewarded” for answers closer to human preference.

This is done at a massive scale inside companies like OpenAI and Anthropic.

Literal armies of labellers go through comparisons all day, every day.

Over time, the model learns:

- What clarity looks like

- What safety looks like

- What a “good” answer is

- What humans hate reading

This is how the model develops its “personality.”

Again — not from the internet.

From people.

C. Tool Use: When the Model Learns to Look Stuff Up

Modern models don’t have to rely only on memory.

Companies train them to use tools by giving them tons of example conversations, like:

User: Who won the Golden Globe for Best Actor in 2022?

Assistant: <search_start> Golden Globe Best Actor 2022 <search_end>

Assistant: Based on what I found...

The model learns:

- When to search

- How to format search queries

- Which situations require external info

- How to pull that info into the conversation

This is why newer models hallucinate way less — they don’t have to guess as often.

In short:

Pre-training gives the model knowledge.

Post-training gives it judgment, tone, and social skills.

It’s the difference between raw internet brain vs. an assistant you’d actually want to talk to.

Why Models Hallucinate?

Even after pre-training and post-training, models still slip up — they confidently state things that aren’t real. This is what everyone calls hallucination, and it happens for a very simple reason:

The model doesn’t actually “know” facts. It predicts what sounds like the next correct token.

If its training data mostly contains polite, confident answers to factual questions, it will imitate that pattern — even when it has no idea what the right answer is.

Picture this:

In the training data, human reviewers answered thousands of questions like:

- “Who is Tom Cruise?”

- “Who is Marie Curie?”

- “Who is Nelson Mandela?”

Every single one of these answers was confident and complete — because the labelers either knew the answer or looked it up.

So when you later ask:

“Who is Orson Kovats?”

…and that name doesn't exist, older models don’t think:

“I don’t know this person.”

Instead, they think:

“Questions shaped like this usually get confident biographies, so let me produce something that fits that pattern.”

And boom — a hallucination.

How do big labs fix this problem?

Companies like OpenAI, Anthropic, and Google actively test their models to figure out what the model actually knows and where its memory is shaky.

The process (simplified):

- They take real text from books, Wikipedia, news, etc.

- They generate factual questions from those passages.

- They ask the model those questions multiple times.

- If the model consistently answers correctly, that fact is “known.”

- If the model gets inconsistent answers or makes things up, they mark it as “unknown.”

Then they create new training examples that teach the model:

“If you don’t know, say you don’t know.”

These new examples get added to the post-training dataset:

User: How many championships did Player X win?

Assistant: I'm not sure — I don't have that information.

Once the model sees enough examples like this, it learns that uncertainty is an acceptable — even preferred — behaviour.

Tool use helps even more

Modern models don’t just shrug and stop there.

They have another move: they can look things up.

During training, companies teach models how to:

- Call web search

- Pull in external documents

- Read the results

- Answer using that fresh info

This is why ChatGPT might briefly say “Searching…” or “Reading the documents…”

It’s using a tool to refresh its working memory, instead of hallucinating.

If the fact exists online and the model is allowed to search, the hallucination rate drops dramatically.

The key idea

Hallucinations aren’t “bugs.”

They’re the natural outcome of a system that predicts text based on patterns.

Big labs reduce them through:

- better post-training data

- explicit “say you don’t know” examples

- teaching the model to use search tools

And even then, no model is perfect.

But the gap between older LLMs and today’s ones is night and day.

Knowledge vs. Working Memory - Why context matters more than “stored facts”?

One of the easiest misconceptions about LLMs is thinking they “store facts” the way a human remembers where they left their keys.

They don’t. At all.

LLMs actually operate with two very different kinds of “memory”:

1) Knowledge in the model’s parameters

This is the stuff the model picked up during pre-training — patterns, associations, and broad world knowledge.

Think of it like fuzzy long-term memory.

It’s not stored as clean sentences like “Paris is the capital of France.”

It’s stored as billions of statistical weights that hint at the structure of language and facts.

This is why models are great at answering common questions but shaky on obscure ones.

If it wasn’t talked about often enough online during training, the model’s “recollection” is weak.

2) Knowledge in the context window (working memory)

This is what you put directly in your prompt.

It’s fresh. It’s exact. And the model can use it instantly.

A good analogy:

Your long-term memory vs. having the textbook open in front of you.

The model does the same.

If you paste the text of Chapter 1 into the prompt, it doesn’t need to “remember” anything — the answer is right there in its working memory.

And this difference explains a ton about how LLMs behave:

- If you don’t provide context, the model pulls from its vague recollections.

- If you do provide context, the model becomes dramatically more accurate — because it’s not guessing, it’s reading.

- When a question hits a gap in its long-term memory, that's when hallucinations appear (unless post-training taught the model to say “I don’t know”).

Modern models like GPT-5.1, Claude 4.5, and Gemini 3 have far more capacity in both areas — much bigger context windows and much richer parameter-based knowledge — but the fundamental split remains the same:

What the model “knows” vs. what you just told it.

Keeping that in mind makes you instantly better at prompting. If something matters, put it in the context window.

Don’t expect the model to recall it from thin air.

So... What Does This All Mean?

If you've made it this far, you now understand more about how LLMs work than most people who use them every day. And honestly, that's the whole point.

You don't need to become an AI researcher to get value from this stuff. But knowing what's actually happening under the hood changes how you interact with these tools.

When the model confidently gives you a wrong answer, you'll know why — it's pattern-matching, not thinking. When it nails something complex, you'll understand that too — it's drawing on statistical patterns from billions of examples. When it says "I'm not sure," that's not a bug. That's the result of deliberate training to make it more honest.

Here's my main takeaway: these models are incredibly powerful, but they're not magic. They're not thinking the way you and I think. They're doing something else — something genuinely useful, but also genuinely different.

The more you understand that difference, the better you'll be at using them. You'll write better prompts. You'll know when to trust the output and when to double-check. You'll stop getting frustrated when the model "misunderstands" you, because you'll realize it was never understanding you in the first place — it was predicting what tokens should come next.

That's it. That's the whole thing.

If you want to go deeper, I really do recommend watching Andrej Karpathy's full lecture. This post is just a summary — he goes into way more detail, with visuals and examples that make everything click even more.

But if you walked away from this with a clearer mental model of what's happening when you type into ChatGPT... then I did my job.

Now go use that knowledge.

.svg)